1. Axioms

Let’s start at the bottom. Axioms are assumptions that form the basis of a Theory. These axioms will not be defended here. The Theory simply takes the form “If these axioms are true, then here’s what follows.”

After much contemplation, my philosophy currently rests on 3 axioms:

A. Stuff exists

B. Patterns are real

C. Things change

A. When I say “stuff exists”, I mean that the term “existence” will be confined to physical stuff, like trees, atoms, photons, etc. I will have more to say on existence when I write about ontology. In contrast, abstractions like numbers do not “exist”, but then

B. Patterns are real. This wording originally derived from Daniel Dennett’s paper “Real Patterns”, but I have come to understand that my use is broader to the point of being platonic (small p). Patterns are simply specific abstractions. Patterns are “mind independent”. The natural numbers are real whether or not anything exists to understand them. Some patterns are discernible in physical things, and all physical things display discernible patterns in their interactions with other things. For example, the number three is discernible in three apples sitting on a table. For everything that exists, there is a set of patterns which completely and uniquely describes that thing, but then

C. Things change. As a framework for this axiom we use David Deutsch’s and Chiara Marletto’s Constructor Theory which says that all physical theories can be expressed in terms of which physical transformations (changes) can be made to happen, which cannot, and why. Thus, all of physics is about how things change.

2. Ontology

Ontology is generally considered the study of what exists. It’s a philosophical area of study because there is no clear cut answer as to what exists. Most agree that trees exist. Does the number “three” exist?

The point of this section is not to argue that the current theory will provide the answer to what exists and what doesn’t. The point of this section is to lay out how this theory will use the terms “exists” and “real”, and to explain how certain fundamental concepts like “causality” and “information” relate to these terms.

Process

The ontology considered here is probably closest to what is called a process ontology. As Philip Goff is fond of saying, physics cannot tell us what things are in themselves, it only tells us what things do, which is to say, how they interact with other things. This doesn’t mean there are no “things” there. It means we can only know about those things by what they do.

Constructor Theory provides a rigorous framework to describe a process (which Constructor Theory calls a task):

Input (x1, x2, … xn) –>[constructor/mechanism/system]–> Output (y1, y2, …ym)

So in the Psychule framework, something exists if it is a mechanism for at least one process. If it doesn’t interact with the environment we cannot ever know about it and would have no reason to care about it.

Patterns

Our axioms say patterns are real. The best explanation of what this axiom is trying to say is probably given by Daniel Dennett’s paper “Real Patterns“. The bottom line is that patterns are real abstract things. This concept is useful to us because our framework relies heavily on patterns. The specific set of inputs to a task constitutes a pattern. The combination of input, mechanism, and output for a given task constitutes a pattern. The set of all input/output combinations for a given mechanism constitutes a pattern. In fact, for anything we identify as existing, we do so by recognizing a set of input/output combinations for that thing, i.e., the patterns associated with that thing, although sometimes recognizing the outputs alone are enough, if those outputs are unique to that thing.

Causality

Causality brings in the topic of our third axiom: things change. Causality is specifically about how things change over time. More specifically, causality is about patterns in how things change.

To my knowledge, causality was most famously addressed by Aristotle and his Four Causes. Over time, causal analysis got whittled down to just cause and effect. I think this whittling was unfortunate because Aristotle’s analysis was accurate, more descriptive, and therefor more useful. Aristotle recognized four causes: the material, efficient, formal, and final. However, instead of calling these “causes”, I think they would be better described as aspects of causation.

His paradigm case was the creation of a sculpture. The material cause was the material from which the sculpture was made, say, clay. The efficient cause was the sculptor. The formal cause was the result, say, a statue of a man. The final cause was the reason the sculpture was made, say, as a contract from the city.

It should be quickly obvious how Aristotle’s framework applies to the current framework. The material cause is the input, the efficient cause is the mechanism, and the formal cause is the output.

Input (material) –>[efficient]–> Output (formal).

The final cause will be addressed in the upcoming section on purpose/function.

The current framework describes causality as follows: a given mechanism causes an output when presented with the input. I should point out that causality as described here is relative. You could just as easily reverse the role of the input and the mechanism, saying a given input, when presented with the mechanism, causes the output. That’s why, I presume, in the standard discussion of “cause” and “effect”, the input and mechanism are lumped together as “the cause”. But breaking them out let’s you focus on one (think of the many different things a given artist could make) or the other (think of the many things different artists could make from a given lump of clay).

Information

There’s another aspect of causality which is important. It follows from any system which at least seems to be governed by rules (like physical laws) that every interaction generates correlation. In the absence of any interactions outside the given system, output is correlated with both the input and the mechanism which created it. Also, if there is more than one output, those outputs may be correlated w/ each other. This correlation is the essence of information. At the level of quantum physics, this property is referred to as entanglement. In Information Theory this property is referred to as mutual information. This mutual information is a physically derived relation between physical systems, and therefore is mind independent. But also note that the physical properties of an isolated system say nothing about its correlations.

Note that there is a value for the mutual information between any two physical systems. So there is a value for the mutual information (MI) between systems A and B, and a different value for the MI between that same system A and system C, and so on. There is a value for the MI (mutual information) between A and every other conceivable system. So where does that leave us? Not all MI values are equal. For example, the MI between smoke and a fire is fairly high, whereas the MI between smoke and a rabbit is lower [but not necessarily insignificant, if there is a rabbit cooking over the fire]. But the MI between smoke and the credit card in my wallet is almost certainly negligible [but not zero!].

To restate: we said a mechanism causes the output when presented with the input. We can also say that a mechanism causes the output to be correlated with both the input and the mechanism. Thus, a mechanism causes information.

Computation

Much heat (and not so much light) occurs in discussions of the relation between consciousness and computers. Here I simply want to establish the ontology of computation with regard to the Psychule framework.

Computer theory has established that all computation can be reduced to some combination of four basic operations: COPY, AND, OR, and NOT. There are other operations, such as EXCLUSIVE OR (XOR), which means something like “x OR y, but not both”, but operations such as XOR are can be organized by combinations of the first four.

[Actually, you can build all computation from just two of these operations: NOT and AND. For example COPY can be made from 2 NOT’s (your basic double negative). Similarly, “a OR b” is equivalent to “NOT ( (NOT a) AND (NOT b) )”. This is why you can build any computer system w/ just NAND gates.]

So what is the significance of computation in the Psychule framework? Computation processes mutual information. Assume x is a physical system that has some mutual information with respect to y. After the operation x COPY, the output of that operation, say z, now has (approx.) the same mutual information with respect to y. In fact, we can define COPY as any operation for which the output retains the same mutual information as the input. Likewise, the NOT operation produces output that has an inverse correlation with respect to the mutual information of the input. The AND and OR operations similarly produce outputs with mutual information relative to the inputs, but the mutual information of separate inputs is combined into the output.

Bottom line: information and computation can be physically described without reference to meaning, intentions, or minds. But then, where do these things (meaning, intentions, minds) come from? Mutual information is an affordance for these things. If x has mutual information with respect to y, and some system “cares” about y such that it “wants” to do a given action when y is the case, then that system can achieve that “goal” by attaching the appropriate action to x.

3. Function

There are two different concepts of function that will be important to us. The first is the mathematical concept: a relation between a set of inputs and a set of permissible outputs with the property that each individual set of inputs is related to exactly one output. [From Wikipedia]. Thus, given the current framework, any process can be considered a function wherein the mechanism is abstracted away, leaving only the inputs and associated outputs. The important takeaway here is multiple realizability. Any physical process is potentially multiply realizable as long as we only care about the inputs and outputs.

The second concept of function refers to working or operating in a proper or particular way. Thus, we say the function of the eyeball is to relay visual information to the brain. When referring to this concept of function we sometimes use the terms “purpose” or “goal”, and we usually associate it with a particular physical mechanism. Note that this “purpose” is not intrinsic to the mechanism. Instead, “purpose” is part of an explanation of why the mechanism came to exist.

Goals

There are some physical systems which, by their organization, tend to move the environment toward a particular state. These systems have been described as cybernetic, and include lightning, vortexes, rivers, etc. A subset of these systems can create new mechanisms, which mechanisms can contribute to the goal (target state) of the creating system.

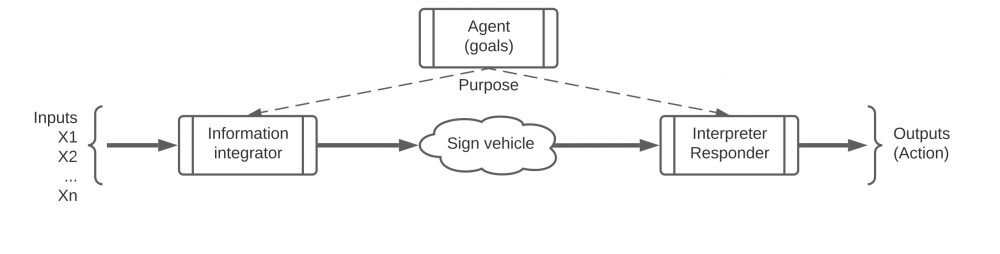

[diagram here]

Natural selection is such a system. The mechanisms thus created can be said to have the purpose or function or goal of moving the environment toward the goal state associated with the mechanism-creating system. For natural selection, that goal state is the out-of-equilibrium state of an existing creature. But this function generally requires the mechanism to be situated in a specific context. If you take the mechanism out of this context it is likely to lose the “purpose” sense of function while potentially retaining the mathematical sense of its function. So, a heart has the purpose of pumping blood, but only so long as it is situated in an animal. Mechanisms can also be re-purposed (exapted). Consider a computer being used as a door stop, or paperweight.

Some people will object to assigning “purpose” to naturally occurring mechanisms, as they consider “purpose” to be associated only with the intentions of an intelligent agent. But “purpose” (or “goal”, etc.) is the closest existing term to describe the concept in question, and so some of us add the descriptor “teleonomic” when referring to naturally derived purpose, and “teleologic” when referring to the intentional purpose of a mechanism created by an agent. Richard Dawkins, when addressing this issue, used the term “archeo-purpose”, but apparently that didn’t catch on, so we’re going to go with teleonomic. Actually, we prefer to just drop the extra term, as teleologic purpose is just a meta-teleonomic purpose. But we’ll use “teleonomic” when pressed.

Finally, I get to point out that function in the sense of purpose, either teleonomic or teleologic, is Aristotle’s final cause. Recall that in the framework:

Input1 -> [mechanism1] -> Output1

Input1 is the material cause, [mechanism1] is the efficient cause, and Output1 is the formal cause. So how does function fit into the framework? Consider

Input0 -> [mechanism0] -> Output0 = [mechanism1]

Aristotle’s final cause derives from a first mechanism which creates/selects a second mechanism of interest, assuming there is some sense in which the first mechanism tends to move the environment toward a goal state by creating mechanisms that do so. The second mechanism would be said to have the goal state of the first mechanism as its “purpose”.

4. Meaning

We said earlier that all matter carries mutual information. So a physical system x that exists now may have mutual information with respect to a physical system that existed in the past, also exists now, and/or will exist in the future. This mutual information is an affordance which can be used by a system to gain value, i.e., move the environment towards a goal state, i.e., serve a purpose. A separate system Z can thus respond in effect to system y (which is distant in time and/or space) by responding in fact to system x.

So, for example, a bacterial food source may generate particular sugar molecules which diffuse away from the source. (The source “causes” sugar molecules which float away). If a bacterium has a mechanism to move to toward this source it will improve its chances of survival. Given that the sugar molecules have mutual information with respect to the source, by utilizing a mechanism that responds to the sugar molecule, the bacterium can achieve it’s goal,of moving closer to the food source.

So we can say mutual information is an affordance for meaning. The *meaning* of theinformation is determined by the mechanism which generates the response (output) to the information in the input. We say that the meaning is generated by the mechanism which interprets the input by generating an output specific to that input. This output constitutes the “meaning” associated with the interpreting mechanism.

Note that the same system X with mutual information(MI) with respect to Y can have different meanings to different responding systems, depending on the specific responses. To a system that responds to X by moving closer to Y, the “meaning” of X is “move closerto Y”. A different system may respond to X by moving farther from Y, in which case the “meaning” of X is “move farther from Y”. It is also true that the same system X can have different mutual information with respect to different responding systems. X may have significant MI (mutual information) w/ respect to Y, but also have similar MI with respect to Z. For example, if I am in a small Japanese village and see a handwritten sign saying “Come in for the best food for miles around!”, I can respond to the mutual information this sign has with restaurants (if I’m hungry), but I can also respond to the mutual information this sign has with native English speakers (if I’m in need of someone who speaks English). So the “meaning” of X depends on the specific response and the system which that response “cares” about.

5. Representation (the Psychule)

First, a quick primer on Charles Peirce’s semiotics. For Peirce, a “sign” is a process which has 3 main components: 1. the object, 2. the sign vehicle, and 3. the interpretant. These correspond pretty much exactly with the elements of “meaning” described above. Specifically, the “object” is what we called system Y, the sign vehicle is what we called system X, and the interpretant is the specific response to X. It will be more intuitive to describe representation using Peirce’s terminology.

The term “representation”, like function, is frequently used in two related but different senses. Sometimes it refers to the physical thing, or sign vehicle, which does the representing, as in “a stop sign is a representation”. Sometimes the term refers to the act or process of representing, in which case there needs to be someone or something interpreting the representing object. The distinction is significant because the question arises in philosophy as what counts as a representation. If you put information on a disk and shoot that into space (as has happened), does that disk count as a representation, assuming there is in fact no intelligent life out there, and so no one for the disk to represent “to”?

For our purposes we will say representation is the act of representing, and that a vehicle designed for the purpose of representing is an affordance of representation, and that representation happens when said vehicle is used/perceived as a representing vehicle.

To express this in the current framework we have to describe two separate processes (tasks). The first task is the process of creating the representing vehicle, which is the output of the task. This vehicle will have mutual information as determined by the computational functions inherent in the creating mechanism and its inputs. We call this vehicle a representing vehicle if the sole purpose of the vehicle-creating mechanism is to generate a vehicle that carries that mutual information to be used in representation.

The second process involved in the “representation” is the one which takes the representing vehicle as input and generates some output which is valuable relative to the mutual information associated with the vehicle. We would call this an interpretation of the representation. Remember that there could be multiple processes which respond to the same vehicle. The “meaning” of the representation is determined by the mechanism which is doing the interpretation.

For what it’s worth, this two step process is what I call the Psychule. My claim is that this process is the common denominator of any good theory of consciousness. This process explains the “aboutness” (via mutual information) of experience. I claim that all currently popular theories of consciousness (with the exception of panpsychism) will necessarily include such processes. And as for panpsychism, the Psychule theory is a panprotopsychist theory, in that all matter has the fundamental property of mutual information simply by adhering to the laws of physics, and this property is the affordance of consciousness via the psychule.